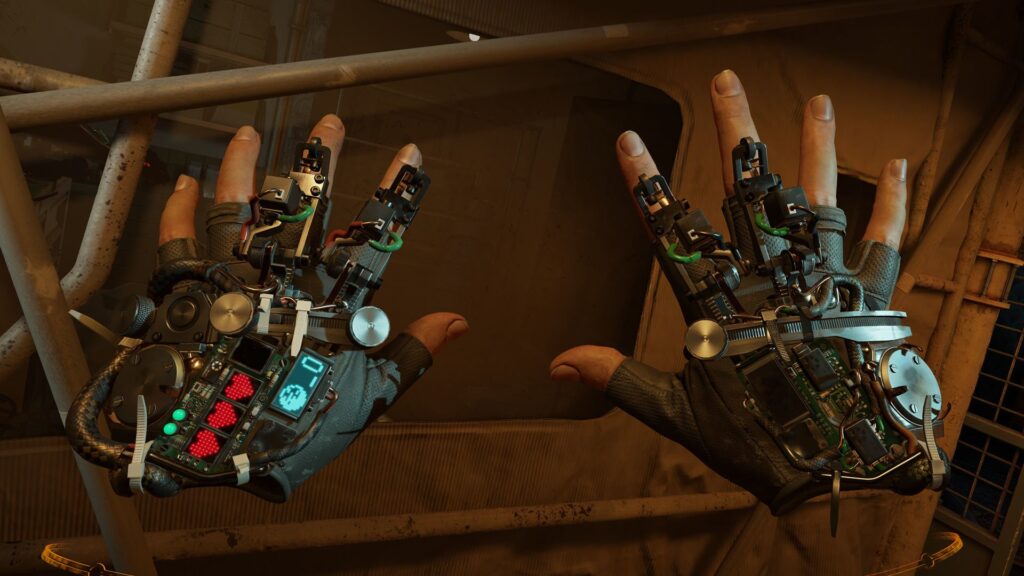

Half-Life: Alyx, which launched yesterday to rave reviews, will give the consumer VR market (a sector which most objective outsiders and investors would describe as having been on life-support for the last several years) a second chance at becoming the consumer entertainment phenomenon that many hoped and expected it to be.

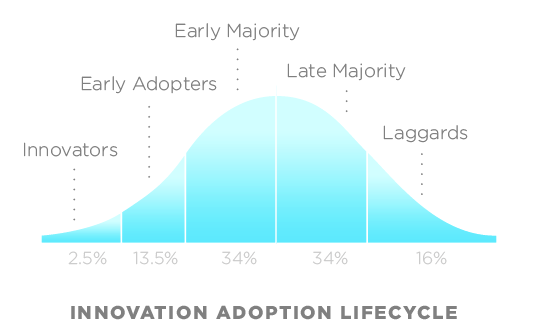

To understand why this is true we must look back at what happened to the market for consumer VR during the last 5 years in the context of the classic “technology adoption lifecycle.” This “sociological model…describes the adoption or acceptance of a new product or innovation, according to the demographic and psychological characteristics of defined adopter groups,” and is illustrated by the graphic below:

The basic idea is that new technologies are adopted in phases, by groups of consumers with different characteristics. Particularly relevant to this discussion are the first two groups:

Back in 2014, when modern consumer VR really “launched,” with the release of the Oculus Rift and HTC Vive, the Innovator segment jumped on-board, as expected. Unfortunately, with price tags of $800+ (not counting the need for a high-end gaming PC that could add another $1000 or more to the total cost of ownership), these headsets were prohibitively expensive for the vast majority of the “Early Adopter” group. Normally, this is to be expected and would have resulted in slow but steady market growth over the following several years, until hardware costs dropped naturally to levels that would have been accessible to most Early Adopters (sub-$400).

Unfortunately, large corporations (Samsung and Google, in particular) realized that their existing smartphone devices could be shoe-horned into cheap plastic (or cardboard) shells with lenses in order to deliver experiences that could be described as “VR.” Despite being severely constrained in nearly all aspects of the user experience (screen resolution, refresh rate, battery life, comfort, rendering power) and offering only 3 degrees of freedom, these solutions allowed these companies to take advantage of early consumer enthusiasm by being first-to-market with “VR” products at prices that were far more accessible (often below $200, and in some cases effectively “for free”).

Unsurprisingly, these solutions offered unimpressive, gimmicky, experiences that delivered relatively little immersion or interactivity and, in many cases, were good as little more than low-res 360-video viewers. Pale shadows of what was available on more expensive, high-end, devices they, predictably, disappointed most of the Early Adopters who invested in them and were quickly cast aside, having failed to generate a self-sustaining market. In so doing, Google and Samsung unwittingly (I hope), “poisoned the well” and left countless Early Adopters convinced, once again, that modern VR wasn’t worth their time (or money).

Later, when the market for high-end VR hardware finally reached a point where viable consumer products, such as the Oculus Quest, were available at reasonable prices, consumer interest had waned significantly. Although Oculus reports that sales of the Quest have been strong, and impressive (but platform-exclusive) full-fledged games like Asgard’s Wrath and Stormland are now available, VR is a segment that remains largely ignored by most gamers, who see little incentive to reinvest in the medium. (“Fool me once,” after all…)

Enter Valve.

Despite having made some of the most influential, critically acclaimed, and well-respected games in history, Valve is not primarily a game maker. Since the early-2000s they have been primarily a market maker, earning their staggering revenue from selling other companies’ games via their Steam digital distribution platform. Valve’s unchallenged dominance of the market for PC-based games has allowed them to take a radically “open” approach to their VR strategy, happily supporting HMDs from their “competitors” on Steam and ensuring that their own VR content supports a broad array of devices from other manufacturers.

It’s clear that Valve has surmised (probably correctly) that a booming VR games market will be good news for them, regardless of whose hardware consumers are using, just as has been true with regards to traditional PC games. This philosophy also explains the strategy behind Valve’s own VR product, the Index. Widely considered the best-in-class consumer VR HMD, comments from the company, as well as the device’s name (and it’s eye-watering $1000 price tag) indicate that Valve sees it more as a benchmark for other manufacturers to aspire to and measure against, rather than a serious attempt to capture market share.

Yet, as is the case with all media, content is king. And, thanks to the lessons learned from Google and Samsung, gamers won’t buy another piece of expensive VR hardware simply due to marketing hype, technical specs, or the promise of great experiences to come. There must be a killer app.

Fortunately, few (if any) IPs can claim as much credibility with hardcore PC gamers as Valve’s Half-Life series. This venerable franchise has represented the pinnacle of gameplay, innovation, and quality to the PC gaming market since the late-90s and it is no coincidence that Valve chose to make Half-Life: Alyx, the first full-fledged new title in the series since 2007’s Half-Life 2: Episode 2, a VR-exclusive.

Make no mistake, this is a bold and unambiguous statement by Valve to the hardcore PC gaming market. To the PC gamer who feels burned by Google or Samsung, it says, “It’s time. You can come back now. You can spend your money on this medium with confidence. If you spend the money to buy the hardware necessary to play this kind of game you won’t regret it, and we are backing that up with the Half-Life brand. (Of course, the BEST version of that experience will be on the Index, where the game will be free, but if you buy ANY of the supported HMDs, you can be confident that you are investing in hardware that will support truly transformative gaming experiences).”

And, by all indications, the PC gaming market has heard the message. Half-Life: Alyx received significant pre-release coverage from a traditional gaming press that has largely ignored the VR segment in recent years and the Valve Index has been sold-out globally more-or-less since the game was announced. One need look no further than the original Halo: Combat Evolved for proof that hardcore gamers will adopt new hardware platforms in order to play a single game if that game is compelling enough.

Half-Life: Alyx will be that game for consumer VR. It represents the market’s re-emergence from the “trough of disillusionment,” accurately predicted by Unity’s John Riccitello. It will bring back the critical Early Adopters who were disappointed by mobile VR, and begin the rebirth of the consumer VR market.

Thanks to Valve and Half-Life: Alyx, 2020 will be an exciting year for VR.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.

GameDaily.biz © 2025 | All Rights Reserved.